I believe there is much to be gained from knowing the past, but what was it that you were looking for when you first began this research/reflection? And what are your personal interpretations and conclusions from this research?In the beginning, I was looking at old electronic instruments mainly to understand how they were built. Since electronics from the 1960’s built for audio frequencies are generally far less complicated than modern electronics built for gigahertz frequencies, I found them a good place to start building up my knowledge base about how to make things. Eventually, I became just as interested in why these instruments were built as in how they were built. I think that is the real core of media archaeology: to look not just at the engineering side but at the cultural side as well, and figure out what cutting edge technologies of other eras represented to people since that helps us understand what kind of utopian ideas we project onto technologies of our own era.

Why did you become interested in audiovisuals after having worked with electronic instruments for so long?I have actually worked in audiovisual configurations for a very long time already. Some of my earliest performances starting in 2003 were playing live processed field recordings alongside live processed video created by one Dutch artist of found objects and footage from the same locations. There is also the obvious visual connection of playing instruments which most people have never seen before, and trying to create a performance which opens up that process and makes it comprehensible.

I performed with optical sound sensors on an overhead projector in the TONEWHEELS project for several years. This idea came from the history of cinema and the optical soundtrack on motion picture film. In the early 20th century, many artists (particularly in the former Soviet Union, but also people like Norman McLaren in Canada and Daphne Oram in the UK) used this technique to create synthesized sounds by painting or photographing abstract shapes directly on to film stock and either running it through the projector or scanning it optically with a CRT.

TONEWHEELS Macro-video recorded by Jérôme Fino/Eyes_For_Ears at Styx Project Space Berlin, Nov 2008. Eyes_For_Ears released a high-contrast, black and white version this video on his own Vimeo page (vimeo.com/jrm).

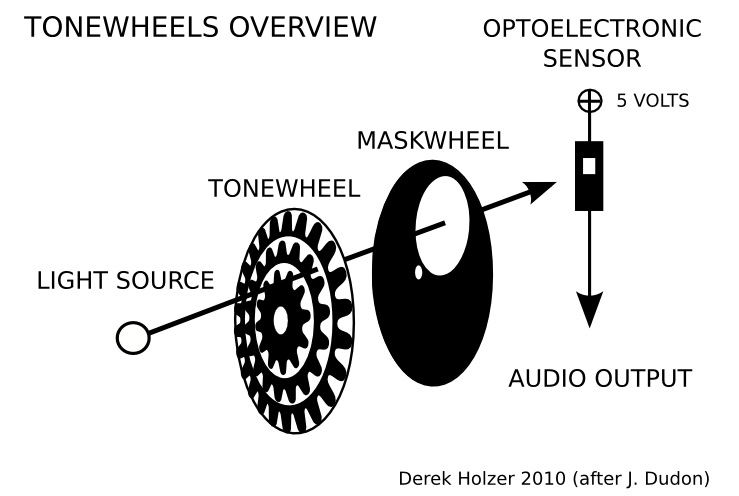

TONEWHEELS is an experiment in converting graphical imagery to sound, inspired by some of the pioneering 20th Century electronic music inventions. Transparent tonewheels with repeating patterns are spun over light-sensitive electronic circuitry to produce sound and light pulsations and textures. This all-analog set is performed entirely live without the use of computers, using only overhead projectors as light source, performance interface and audience display. In this way, TONEWHEELS aims to open up the "black box" of electronic music and video by exposing the working processes of the performance for the audience to see.

Derek Holzer: sounds, electronics umatic.nl/tonewheels.html

TONEWHEELS is an experiment in converting graphical imagery to sound, inspired by some of the pioneering 20th Century electronic music inventions. Transparent tonewheels with repeating patterns are spun over light-sensitive electronic circuitry to produce sound and light pulsations and textures. This all-analog set is performed entirely live without the use of computers, using only overhead projectors as light source, performance interface and audience display. In this way, TONEWHEELS aims to open up the "black box" of electronic music and video by exposing the working processes of the performance for the audience to see.

Derek Holzer: sounds, electronics umatic.nl/tonewheels.html

Figure III

Derek Holzer, Tonewheels system, 2010.

Quoted from Vector Synthesis: A Media Archaeology of Sound-Modulated Light (Page 36) by Derek Holzer

Derek Holzer, Tonewheels system, 2010.

Quoted from Vector Synthesis: A Media Archaeology of Sound-Modulated Light (Page 36) by Derek Holzer